The Isle of Purbeck Sub-Aqua club has won a national award for work towards solving the mystery of the ‘bumps in the bay’ that has puzzled geologists for years.

The award, presented by the Duke of Cambridge at a ceremony in London, recognises outstanding achievement in the field of scuba diving.

Chairman of the club Nick Reed described the unique project as ‘diving with a purpose’.

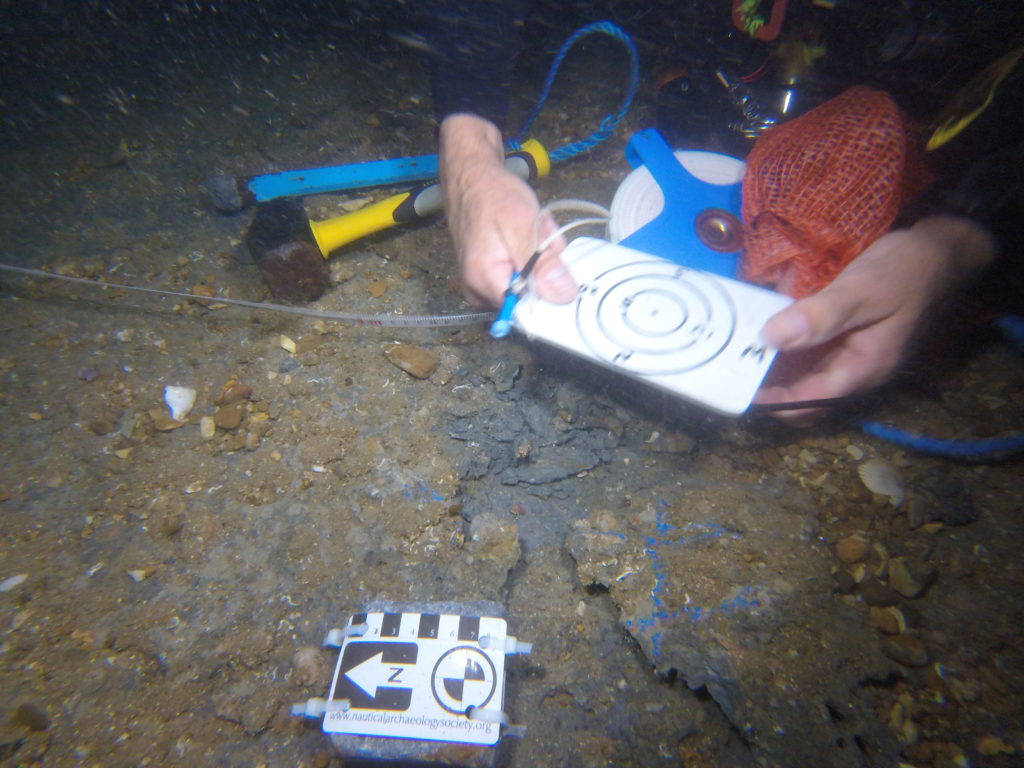

The project to take samples from the seabed is described as ‘diving with a purpose’

Mystery from age of dinosaurs

Project team leaders, Peter Mensikov and Christopher Dunkerley, along with team members Stephan Spiriak, Keith Coombs, Jeremy Goodall, Nick Reed and Dan Bosence went to Kensington Palace to receive the award given by the British Sub-Aqua Club.

The project, which started in 2018, conducted a diving investigation of a geological mystery from the age of the dinosaurs.

The geology is explained to team members

“Pretty unusual”

Nick Reed said:

“As a dive club we try to adopt a project-based approach. What can we do, rather than just dive?

“You get a lot of people looking at shipwrecks and that sort of thing, but to investigate a geological aspect is pretty unusual.

“It’s recreational divers using their diving to answer scientific questions. It’s diving with a purpose.”

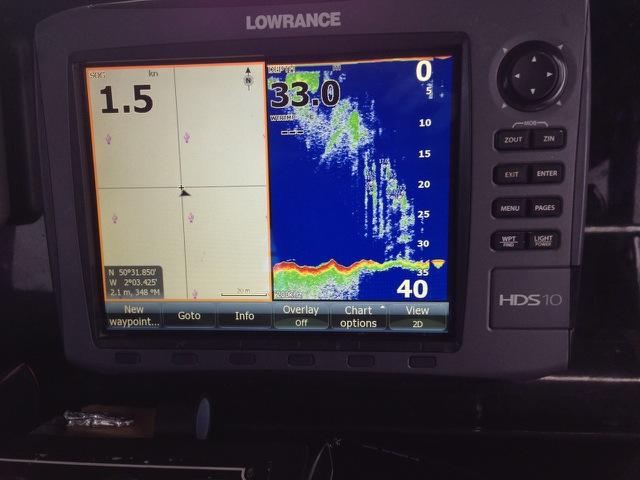

Using sonar the divers can locate the right places to dive

Sonar surveys

It all started when a couple of club members went to a talk at the Etches Collection in Kimmeridge given by Professor Dan Boscence, geologist and professor emeritus at Royal Holloway University.

Underwater sonar surveys had revealed large circular structures in the Purbeck limestone which have not been seen on land in any of the coastal cliffs or quarries despite over a hundred years of geological research.

The structures were 120 metres in diameter and four to five miles offshore between Durlston Head and halfway across Weymouth Bay.

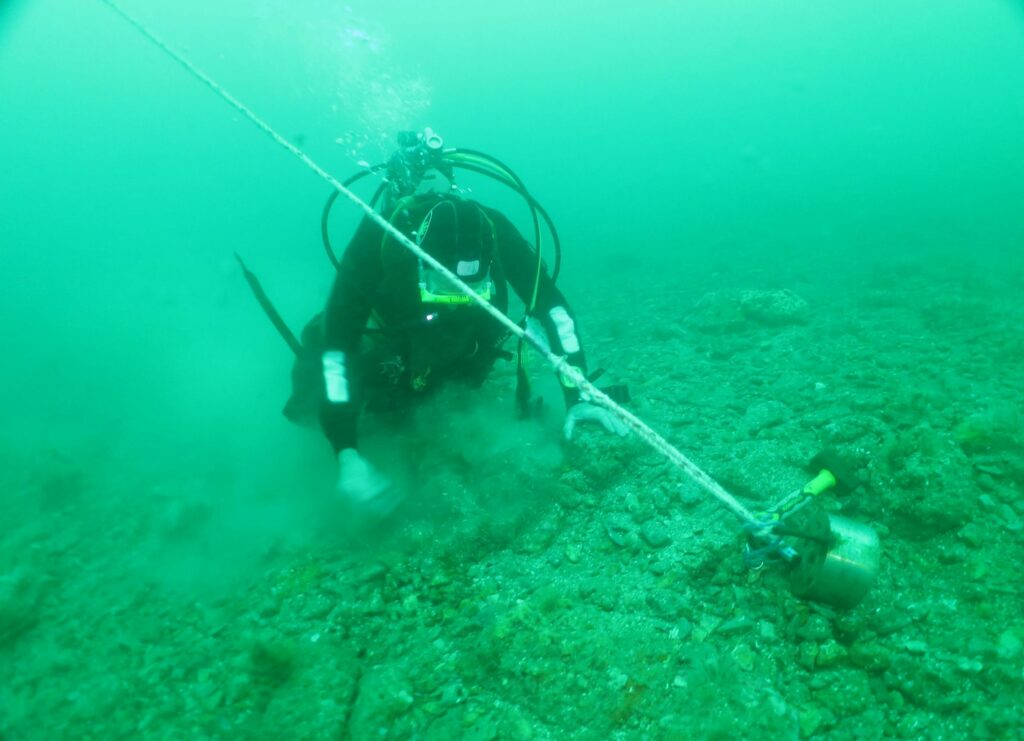

Teams of about six divers at a time took part in the work

Difficult diving

An initial analysis generated seven hypotheses for the origin of these structures but with no way of narrowing the field without diving for samples.

At the end of the professor’s talk the club members volunteered their services.

Diving in these waters is exceptionally difficult and required experienced divers going down to depths of 40 metres.

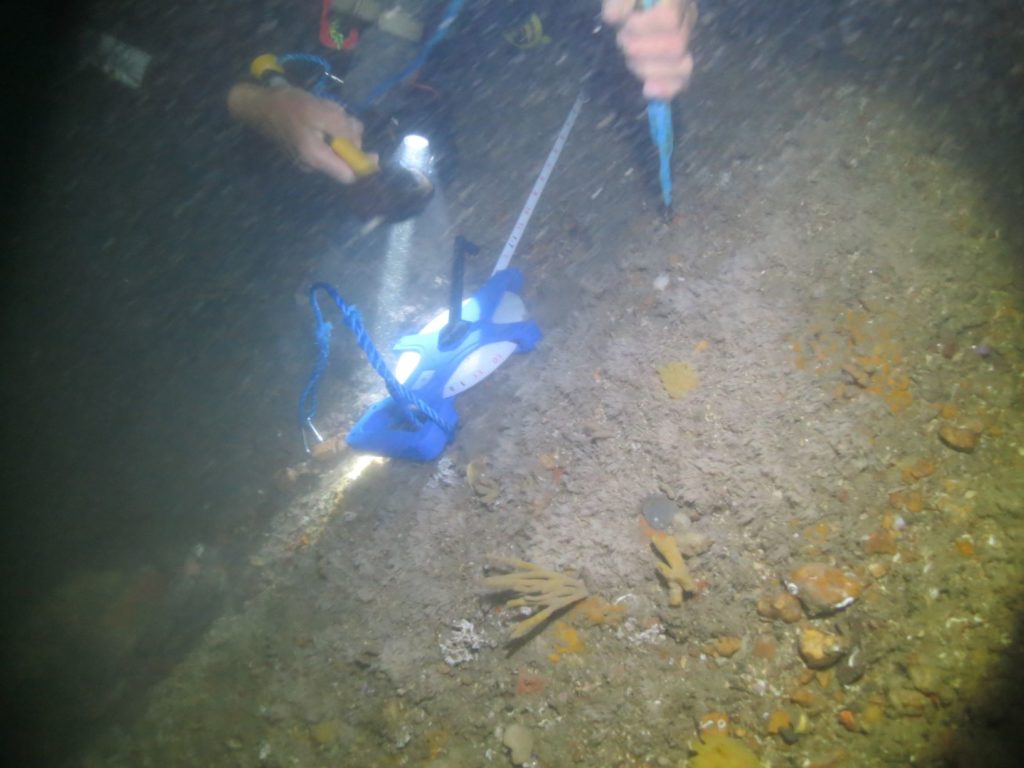

Taking a sample from one of the ‘bumps in the bay’

Team collected samples

In 2019, the team had a field trip to explain what they were looking for including looking at multibeam sonar sound maps. Diving with the diving school Divers Down began as soon as the season started and continued last year despite Covid restrictions, with more this year too.

The team – with funding support from the British Sub-Aqua Jubilee Trust – successfully collected 32 fist-sized samples from seven sites, which were analysed in a laboratory.

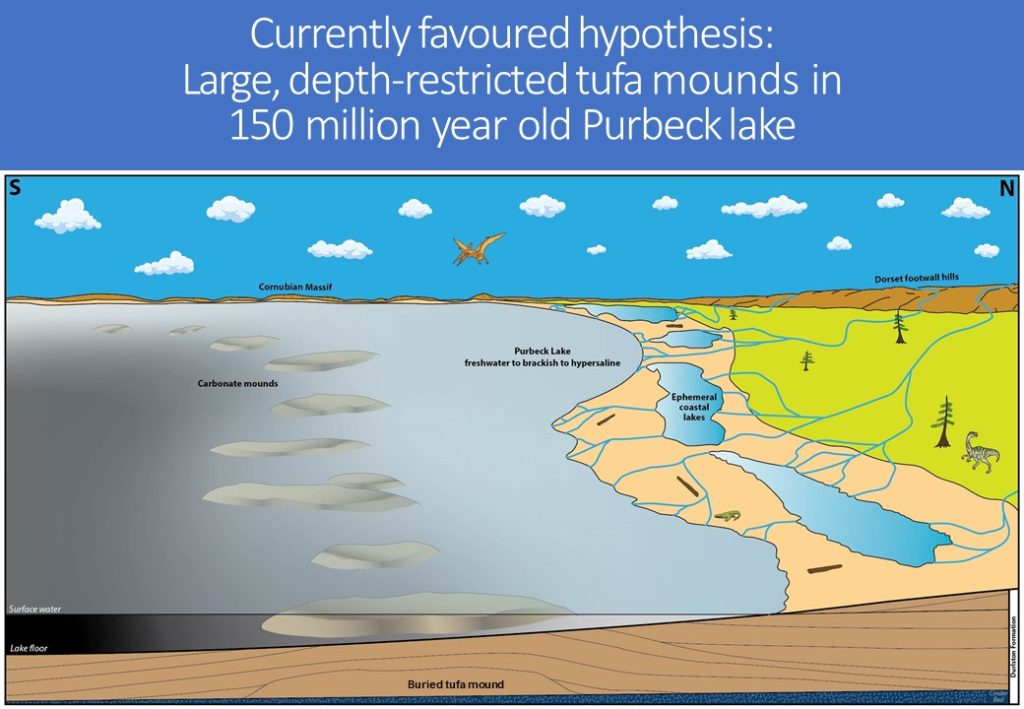

Analysis of the samples allowed geologists a better insight into how the formations came about

One preferred hypothesis

Nick explained:

“The tides are really quite vicious. You have to make sure it is the right tide, and you go out at the right time. There was no decompression diving, so that limited the time underwater to relatively short dives.”

As a result of the findings, seven initial hypotheses have been narrowed down to a preferred hypothesis.

How the area might have looked 150 million years ago

“More questions to be answered”

It’s now thought that around 150 million years, when Purbeck was covered in a warm brackish lake, limestone gradually deposited around biological material becoming what are known as Tufa mounds.

Nick Reed said there was still more work to do on the project:

“Every time you answer a question there are more questions to be answered. So, the project is carrying on and will be on the dive programme for next year.”

Diving on the bumps will continue next year