A photograph from the summer of 1934 of holiday makers along the seafront could hold the answer to Swanage’s split personality, according to the author of a new illustrated history of the town.

Looking along Shore Road, the line of parked jalopies give away the fact that this is almost 100 years in the past, but what the black and white picture disguises is that the string of 1,800 lights along the seafront were – take a deep breath – multi-coloured.

Jason Tomes, author of Swanage: An Illustrated History, with his book

Quiet backwater or brash Bank Holiday resort?

Jason Tomes, who was born in Swanage and is now a lecturer in history and politics, tells the story about the huge row over the ‘wretched’ multi-coloured lights along the seafront, along with many others in his new book Swanage: An Illustrated History. The book features more than 250 photographs and prints from the distant past and from more modern times.

And the over riding theme of the book is how Swanage has seen itself over the years; an industrial town, a rural community, a quiet backwater, a retirement destination, an upmarket genteel resort, or a brash, kiss me quick bank holiday attraction?

Or possibly a bit of everything says Jason, who writes the book with a great deal of affection for his place of birth, as well as including an occasional criticism and a controversial aside.

After spending the first 20 years of his life in Swanage, and still returning for several weeks every year to visit his parents, he felt in an ideal position to write a social commentary on the town with a little historical context.

But with help from Swanage Museum, a wealth of historical documents and photographs, and a lot of time on his hands, the idea grew and became a 200 page book covering everything from Roman quarrying to 21st century centralisation.

White’s bathing machines on the beach in August 1897

Swanage’s first motor taxis firm in 1910, in Ulwell Road

‘Wretched fairy lights’ offended the discerning

And of that defining moment in 1934 which forced Swanage to consider its future, Jason said:

“The idea of multi-coloured lights along the seafront had come from the Bournemouth and Poole Electricity Supply Company, and when they offered free hire of cables and bulbs Swanage Urban District Council (SUDC) yielded to temptation.

“The Chamber of Trade decided that ‘those wretched fairy lights’ offended ‘the more discerning type of resident and holiday maker on whom the town still so largely depends’, while the rector regretted that ‘there would always be those who for selfish greed would mar God’s beautiful creation’.

“SUDC increasingly tolerated artificial attractions, especially when it stood to make money. There had always been a few donkeys on the beach and would be until 1954, as well as motor boats for hire, puppets, and Wall’s ice cream kiosks; but a second illuminated season of multi-coloured fairy lights was ruled out by five votes to four.”

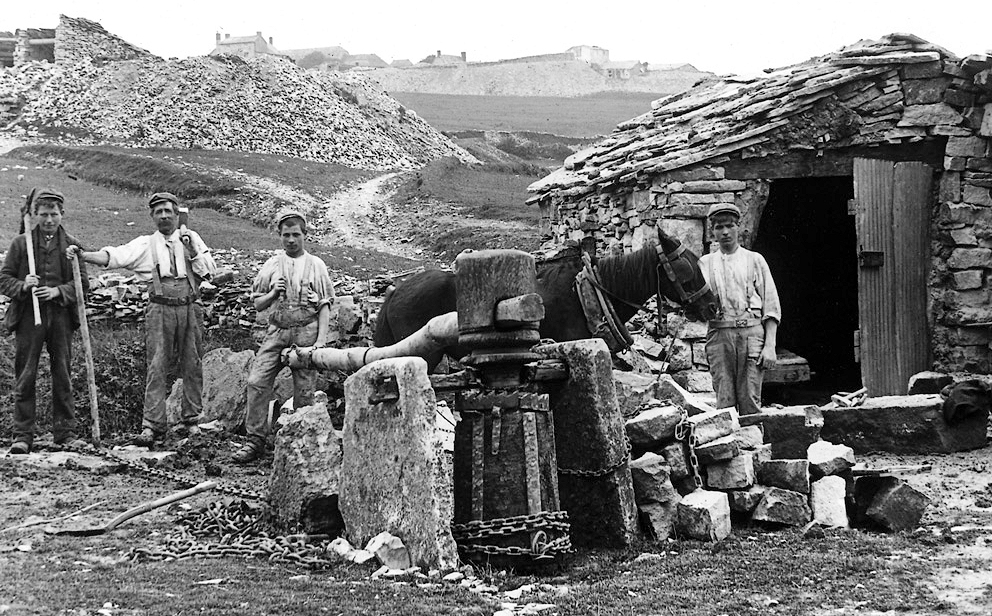

Quarrymen at Herston in 1896 with Belle Vue Farm in the background

A wagon load of stone passes through Herston in 1910

Swanage relied on its quarries for wealth

As Jason says in his new book, Swanage was once very much aware of its place in the world, for despite a coastal setting as beautiful as any in Britain, it was firmly an industrial village reliant on the sea and stone until well into the 19th century.

Quarrying has been carried out in Swanage since at least Roman times, as proven by inscriptions on Purbeck marble (actually polished limestone) to the emperor Nero. The earliest known pictures of the town, from 1790, show a stone pit and blocks waiting to be shipped.

Where Dorset was mainly a county of farmers, Swanage relied on its quarries for wealth; in the 1841 census when 41 percent of men worked on the land, in Swanage there were just 10 farmers and 31 agricultural labourers recorded, as opposed to six stone merchants and 214 stoneworkers.

Attempts from the 1820s to promote Swanage as a health resort ran into many problems, not least was the opposition to the plans of Dorset MP William Morton Pitt, who built the Manor House Hotel and hoped to rival Margate and Brighton as a centre for the gentry to take the waters.

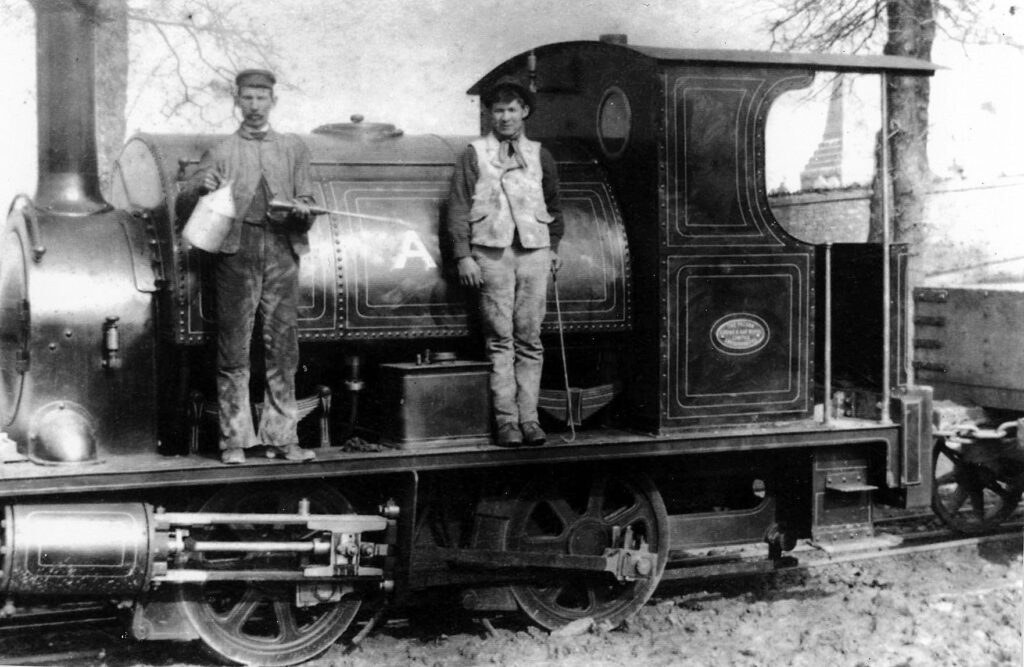

Swanage’s first railway locomotive was hauled by horse from Wareham in 1884

Tilly Whim Caves became a top tourist attraction in late Victorian times

New railway brought 3,000 visitors on one day

Industrial Swanage continued to run alongside early, upper class tourism; as up to 50 cart loads of stone passed through the High Street daily, gouging deep ruts in the muddy road and forcing visitors and other vehicles out of the way – the partnership was not a happy one.

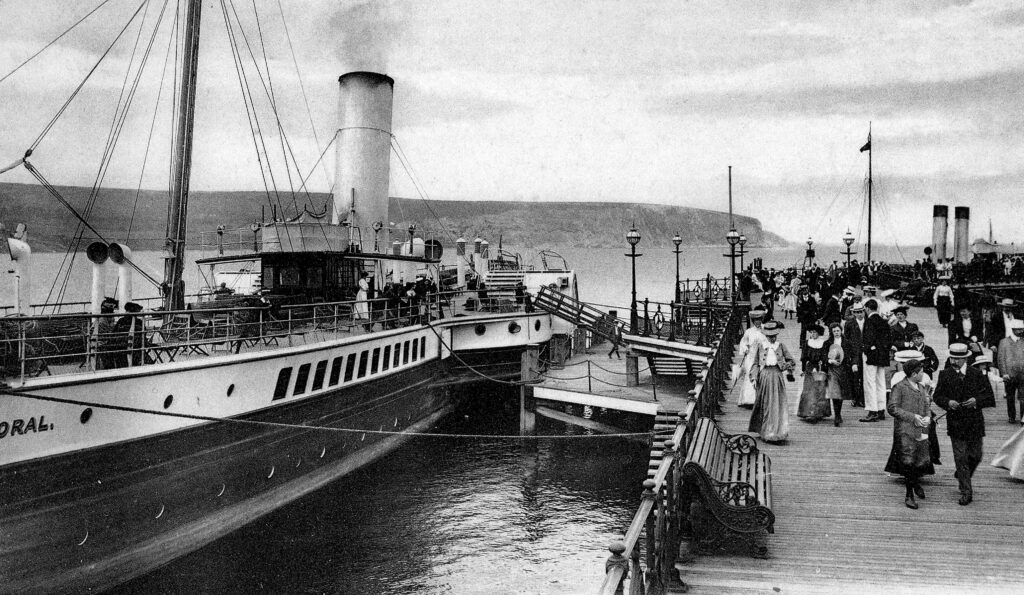

But the arrival of the railway in 1885 put Swanage firmly on the map, transforming it into a popular seaside resort and on just one day, Monday 3rd August 1885, 3,000 visitors arrived by steamer and an equal number by train.

George Burt, a Victorian quarryman turned businessman who together with John Mowlem did more than anyone else to shape Victorian Swanage, saw land prices soar.

Four new roads – Rempstone, Gilbert, Cranborne and Ilminster – were laid out and Burt built a mock medieval castle at Durlston Park, placed a huge globe near it carved out of Portland stone and used explosives to create a new tunnel to the Tilly Whim Caves, all to attract tourists to the town.

Jason describes the usual double-sided Swanage reaction to George Burt by quoting a joke from Punch in 1897:

“In some towns they swear by unmentionable people. At Swanage, they all swear by Burt.”

The paddle steamer Balmoral arrives at Swanage New Pier in 1906

The launch of Swanage’s first powered lifeboat, the Thomas Marksby, in July 1928

All day feast with three gallons of gravy

Jason said:

“It is usual to cite Thomas Hardy, who called Burt the ‘King of Swanage’ but this was a king whose subjects were disinclined to bend the knee.

“He inspired respect as ‘one of us’ who had done very well for himself, but they knew him for the son and brother of stone merchants cum bakers despite his emergence as squire.

“In 1889 he treated the Company of Marblers to an all-day feast with 400 pounds of beef and three gallons of gravy. A thousand people were present when it ended with ‘three such hearty cheers as were never heard in Swanage’.

“Even so, to smash a window at Purbeck House, Burt’s mansion in the High Street, was the reflex of local malcontents.

“Rural purists loathed Burt’s handiwork saying that he tried to improve on nature and committed various atrocities, but the fact remains that Burt determined the town’s destiny by bringing the railway that definitely turned it into a resort.”

Swanage Brass Band in 1864, pictured in the garden of the brewery manager

The Royal Victoria Hotel, pictured here in 1860, did not impress everyone

Town tried for quality instead of quantity

But as Swanage: An Illustrated History makes clear, the town would spend the next century undecided what sort of tourist resort it wanted to be.

By 1928, the town guide was announcing:

“Swanage is but a small town and visitors must not expect the diversions of Margate or Blackpool.”

But it didn’t impress everyone; the Royal Victoria Hotel, which had been the only place for the upper classes to stay since the 1830s, was dismissed by Beatrix Potter as ‘clean, civil, rather poor for the money and singularly tough food’.

As Swanage was too far from any big city to go for the mass market, it tried for quality instead of quantity, which meant offering the middle classes ‘immunity from rowdiness and vulgarity’.

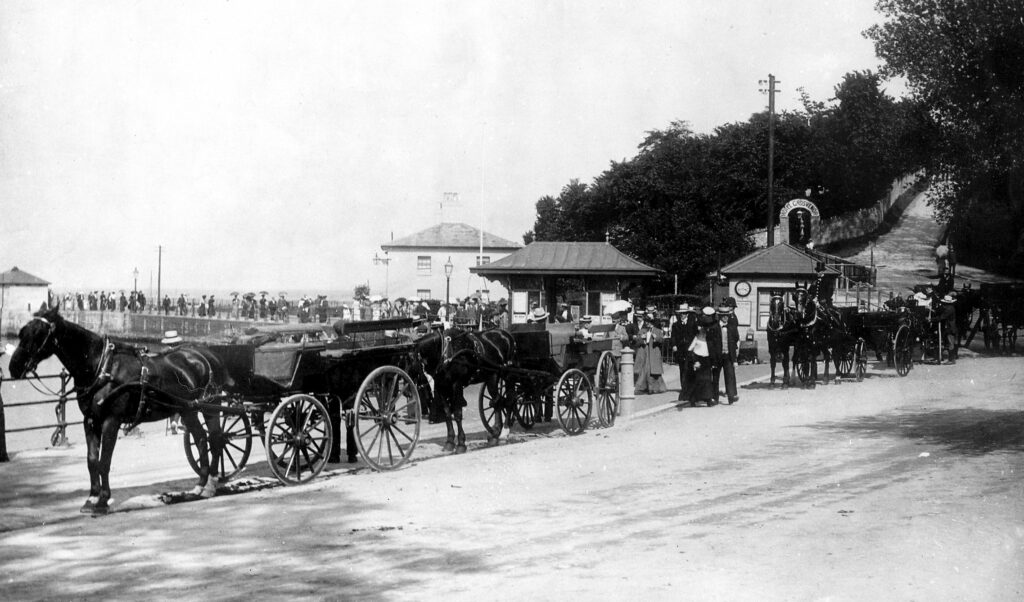

Wagonettes waiting for customers at the entrance to Swanage Pier in 1900

Swanage Beach with bathing huts and deckchairs in 1905

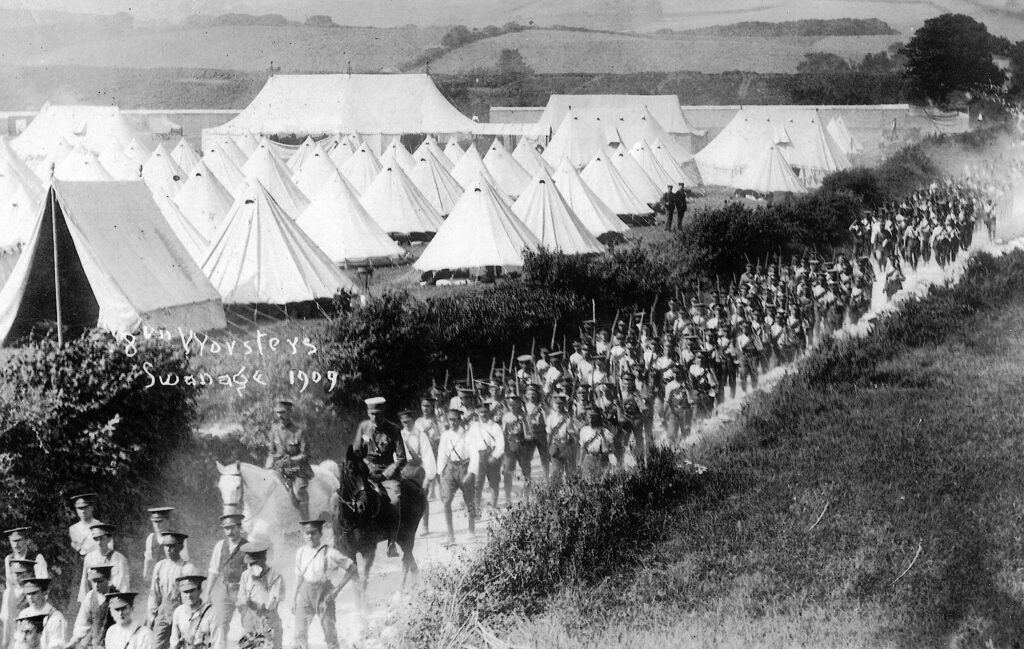

The 8th Battalion Worcestershire Regiment held its summer training camp at Swanage in 1909

“In future we shall shun it like the plague”

But this didn’t stop the creep of one-armed bandits, beach huts, a bagpipe player, fortune tellers on the sands and cinemas. In May 1940, even as the Battle of Britain began, Swanage residents launched a petition against Punch and Judy shows taking place on Sundays.

After World War Two, the growth in car ownership brought a new clientele to Swanage. In August 1957 the Times reported that the worst queue in the country on the Bank Holiday evening was a ten mile stationary line to Wareham.

By 1963 a headline in the Observer read: ‘Having a hell of a holiday – wish you weren’t (all) here’ while the Guardian printed the letter of a Crawley resident who was aghast at what they called the commercial desecration of Swanage: ‘In future, we shall shun it like the plague’.

Bank Buildings in 1905, before it became the Trocadero Restaurant

Station Road flooded by Swan Brook in November 1935

Very poorly served by county histories

Jason said:

“I lived in Swanage from 1966 to 1985, but even after I moved away I kept up to date with what was happening in the town as I came back regularly to visit my parents.

“I wanted to move away as I couldn’t see any employment opportunities in Swanage, but I just viewed it as one of those things and still had a lot of affection for the town.

“Eventually I decided to do some historical research to pass the time while staying with my parents and discovered that Swanage was very poorly served by county histories as it was difficult to fit in with the idea that Dorset was a rural county of thatched cottages with roses round the door.

“Even before tourism, Swanage wasn’t typical of the county, but once it became a seaside resort it became really interesting.”

Modernised in 1907, Swanage Fire Brigade kept its horse-drawn pump until 1925

Coal porter John Gotobed, pictured with his donkey in the High Street, 1895

‘Neither dinkified nor desperate’

Jason added:

“I didn’t want to write a conventional history, I wanted to show Swanage’s individuality and its very different personalities; there are very few industrial towns which became resorts, even if the hoteliers had to fight against indifference and sometimes even outright hostility.

“What I like about Swanage is that it’s hard to pin down; it has not totally reinvented itself and in August it would still be pretty familiar to the way it was in the 1970s and 80s; but at the same time the social tone has moved upwards.

“From the mid 1990s onwards its image did change and papers like The Times, Guardian and Telegraph all started to talk up Swanage quite remarkably as a ‘quiet delight’, one of England’s ‘finest seaside towns’, a compelling place ‘neither dinkified nor desperate’.

“Perhaps it hasn’t changed all that much. People remark that the town doesn’t know what kind of venue it wants to be, but did it ever?

“Part of me likes that Swanage provokes a lot of reaction. It is not a picture perfect postcard village, but it is a rural gateway, artistic, historic and quirky.

“An answer was found to the question of seafront illuminations; the string of lights has now been exclusively white since 2003. A resort, yes – but a tasteful one.”

Further information

- Swanage: An Illustrated History by Jason Tomes is published by Dovecote Press and is on sale from The Swanage Bookshop and other outlets, priced at £15.