The somewhat forgotten story of how Langton Matravers in Dorset helped to win World War Two is being told in the village museum to mark the 80th anniversary of D-Day.

Until Saturday 29th June 2024, the Purbeck Stone Museum behind St George’s Church in Langton Matravers, is recounting the tale of how top secret work in the village to develop microwave radar, paved the way for the success of the D-Day landings on 6th June 1944.

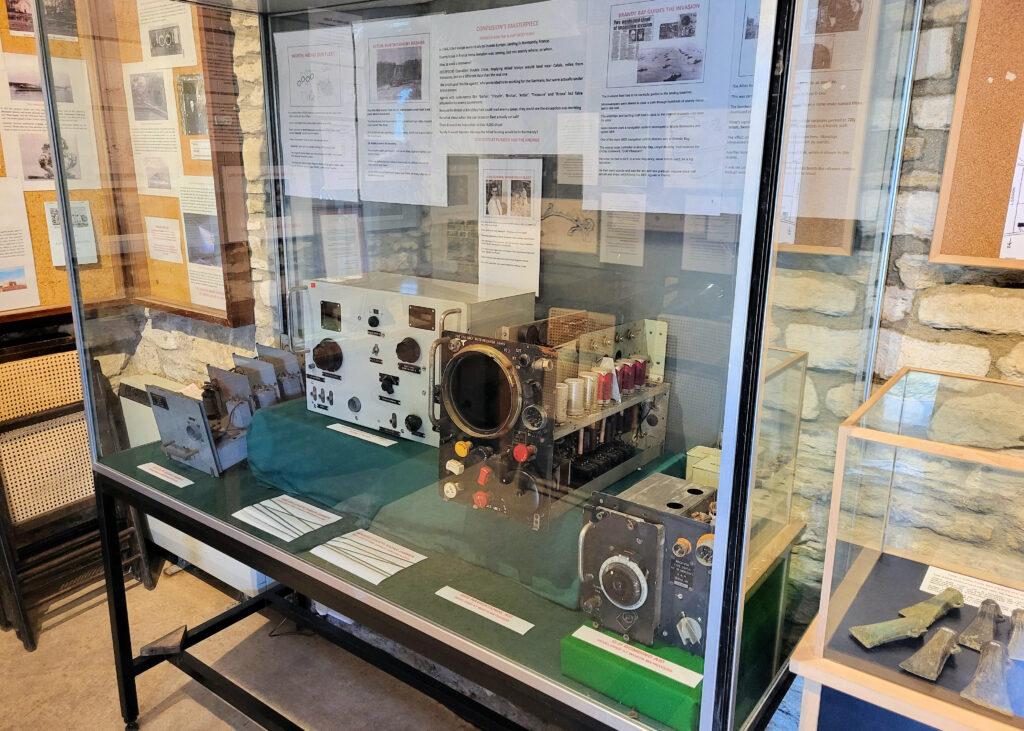

Part of a World War Two display at Langton Matravers museum which tells how radar was developed here

Purbeck’s wartime Silicon Valley

For two years between May 1940 and March 1942, Langton Matravers and nearby Worth Matravers were home to 2,000 of Britain’s top high-tech scientists, with many of them billeted in Swanage and throughout Purbeck.

As the area became the wartime equivalent of Silicon Valley, work carried out on developing and using microwave radar, literally became the key which turned the course of the war.

Thanks to the work being carried out in Purbeck, Britain was able to deal with the German U-boat threat, clear the North Atlantic for the crossing of troops and equipment, and provide safe passage across the English Channel for the invasion force.

Langton Matravers museum curator Richard Cottrell welcomes visitors

Radar was the key to D-Day

Langton museum curator Richard Cottrell said:

“It’s a very interesting and important story which is not well known. Microwave radar wasn’t just important in sinking boats, without it we would not have been able to even consider mounting D-Day.

“It could never have happened but for the actions of a bunch of scientists working in a damp, draughty stable at Leeson House in Langton, the team which was moved away from Worth for greater security.

“They managed to make a microwave radar with high power which provided far more accurate identification of targets, meaning they could pick up the conning tower of a U-boat in a rough Atlantic sea at night from a bomber flying far overhead.

“The Germans had tried extensively to do this and had given up, saying it could never be done, but the team of top scientists working at Langton managed to invent this crazy thing which today is widely used as the basis for a microwave oven.”

Navigational aids combined with radar turned the tide in World War Two

“At one point we nearly lost the war”

Richard added:

“Up until the point that became available to us, the UK was not doing well at all and at one point we very nearly lost the war – in 1942 we lost over 1,000 ships which really frightened Churchill as he knew from his military experience that was not sustainable.

“But radar made all the difference – the Enigma team at Bletchley Park could give a grid square where the U-boats were, but that was 10 miles by 10 miles of rough Atlantic seas.

“After radar, bombers were able to pinpoint them using radar, where previously it had been like trying to find a needle in a haystack.

“Once the system started working, the numbers of U-boats destroyed rose dramatically and the number of Allied ships lost dropped dramatically, to the point that the German Admiral withdrew all of his U-boats from the north Atlantic for a while because he was losing too many of them.”

Thank you Purbeck – the magnetron not only won World War Two, but today also powers microwave ovens

How Purbeck fooled the Fuhrer

This allowed the huge logistic effort that was needed for D-Day to take place, providing safe transport for the huge numbers of Canadian and American soldiers being brought across the Atlantic, as well as the landing craft – every one of which used in D-Day having been manufactured in the USA.

It then became necessary to deceive German dictator Adolf Hitler into believing an Allied invasion would happen anywhere but the Normandy beaches – and once again, Purbeck was at the forefront of fooling the Fuhrer.

False information was fed to the Germans through double agents and then Colossus, the world’s first electronic computer created with help from radar scientists at Worth Matravers, was able to crack German ciphers to discover that the lies had been swallowed.

A Lancaster bomber dropping the radar cloaking system now known as chaff and invented by Joan Curran (inset) at Worth Matravers

Silencing guns from Tilly Whim

Radar spy receivers to disable the Germans’ early warning signals were also developed in Purbeck.

Separately, scientist Joan Curran of Worth Matravers developed a system of dropping aluminium strips from planes which were of such a specific shape that their signals deceived German radar into thinking they came from ships.

A navigational system codenamed GEE, developed at Worth, allowed our minesweepers to clear safe passage across the English Channel for D-Day.

And a scheme to silence the German guns on the French coast by giving British bombers the most accurate guidance possible, was dreamed up at Worth Matravers and operated from Tilly Whim.

Mike Gould, centre manager of Leeson House, Langton, where a plaque commemorates the vital role it played during the war

German reserves arrived too late

Richard Cottrell said:

“Much of the success of the deceptions was the result of a massive amount of creativity under great pressure by the scientists who had worked at Worth and Langton Matravers.

“Although the Germans reacted very quickly to the invasion when it came out of the blue at Normandy, Hitler’s reserves did not reach the battlefields until late in the afternoon of D-Day, by which time it was too late.

“The invading Allies had gained a secure foothold, from which they would advance to liberate France and then western Europe.”

There’s a memorial to Dr Bill Penley, radar pioneer, at St Alban’s Head

Germans never knew of Purbeck’s radar

Richard added:

“By that time, though, the scientists of Purbeck had been sent to Malvern as Churchill was frightened of a German commando raid attacking the site here.

“Ironically, after the war German records showed that they never knew radar was being developed here – although they saw the huge masts here, they couldn’t believe that we would have been so stupid to put them in such a vulnerable position!”

The Langton Matravers museum is better known for telling the story of Purbeck stone

Further information

- The Purbeck Stone Museum, St George’s Close, Langton Matravers BH19 3HZ is open every Monday to Saturday from 10 am to 12 noon and from 2 pm to 4 pm until Monday 30th September 2024

- The D-Day radar exhibit will remain in place until the end of June 2024.

- More information on the Purbeck Radar story